Head of Intellectual Property, Graham Farnsworth, Dstl:

“The Defence Science and Technology Laboratory (Dstl) is a proven national asset that provides innovative solutions to help protect the armed forces and keep the public safe.

It collaborates with experts in academia and industry, particularly small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), to produce pioneering science and technology from cyber and artificial intelligence to robots and military vehicles.

A number of its solutions also have wide ranging benefits beyond defence and security and these opportunities, in addition to exploitation in defence and security, are managed by the Intellectual Property team.

The team have recently reached the milestone of 1000 Intellectual Property (IP) reports and operate under the maxim of ‘highlight, protect, exploit'.

The importance of the team was demonstrated when our new invention uncovered previously unrecognisable fingerprints. The technology was later licensed to Foster and Freeman in 2017, and launched as RECOVER in 2018."

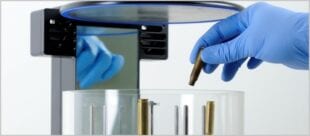

The RECOVER Machine

Before we arrived at this stage, a pioneering technique was found which allowed a fingerprint to be retrieved from a metal object even after it has been cleaned with solvent or burnt in a fire.

This sounds amazing enough before you even find out that this was invented in part by chance, at which point it seems to echo Alexander Fleming’s infamous discovery of penicillin.

However, this is really a story of collaboration and maximising the impact of our knowledge assets.

This story started in a lab at Loughborough University in 2007 where a group of scientists were studying inorganic chemistry.

They noticed that a glass bottle that had been left overnight, and exposed to the process they were using, had developed a fingerprint.

This is now called Latent Fingerprint Technique (LFT) and it can recover fingerprints from items that had previously been extremely challenging or impossible to work with.

This includes items exposed to high temperatures, such as Improvised Explosive Device (IED) components and fired ammunition cases, as well as metal items that had been deliberately cleaned, such as knives.

This clearly has applications to both the battlefield and the crime scene.

The technique used by forensic services to develop and preserve fingerprint evidence is known as a ‘fuming process’. A precursor powder is heated and then allowed to degrade into a crystallised form in a chamber containing the object under analysis.

This crystallised form is then re-evaporated, creating fumes around the object which then condense to develop fingerprints on the sample.

Unlike other techniques, LFT does not require the presence of sweat or naturally occurring skin oils to develop a fingerprint.

Loughborough University collaborated with us at Dstl and the Home Office Centre for Applied Science and Technology (CAST). The latter is now part of Dstl.

Scientists from the university, as the developers, had the fundamental understanding of how the novel chemistry worked.

CAST brought knowledge of the fingerprint development processes used by the police and had also demonstrated success in taking laboratory concepts and turning them into operational equipment.

We at Dstl had a need to improve fingerprint recovery rates and provided funding to drive the development forward.

Together, over eight years, our combined efforts made the LFT technology a viable tool.

It is a fantastic example of collaborative working between academia and government to develop an innovation that will help the police and security services to identify criminals and link them to their crimes.

From an IP perspective, it was important that this opportunity was highlighted early so we could protect it, exploit it and maximise its impact. This way, we retain the use of this technology and its vital capabilities for defence and security, we can help exploit other applications that benefit the wider public and also generate money for the UK economy.

The IP team work closely with Ploughshare Innovations (the commercial sister organisation of Dstl) and is skilled at licensing our technologies and finding the right partners to bring these products to market.

Turning the successful laboratory technique into a commercially available product required the expertise of an industry partner.

Ploughshare’s assessment of LFT identified it as being suitable for licensing and the process of screening potential interested parties began in 2015.

Foster and Freeman, as a leading forensic science equipment supplier to more than 150 countries, was an ideal partner to take this technique and turn it into a successful product.

The company also had 40 years of experience delivering pioneering technology to police and government agencies.

The LFT tech was licensed to Foster and Freeman in 2017 and launched as RECOVER in 2018.

The LFT technology which was launched as RECOVER

Foster and Freeman recognised the laboratory processes would need to be adapted to comprise of a single unit and be, in part, automated.

This collaboration of the right people has ensured that this chance discovery in the Loughborough University lab did not stay in the lab.

We were in a position to remove roadblocks and to ensure the government’s investment in science and technology was maximised and that wider society also benefits by the application of this innovation.

The RECOVER product can get results within as little as 30 minutes and is already being used by forensic teams and experts securing convictions on a global scale. This is another excellent example of powering private sector R&D investment and success through public sector innovation.

Leave a comment