Intangible assets: a trillion-dollar asset class

Recent years have seen a vibrant discussion of intangible assets - things like intellectual property, skills and know-how. Strong contributions have been made by Baruch Lev, in The End of Accounting; Carol Corrado, Charles Hulten and Daniel Sichel, in Measuring Capital in the New Economy; and by Jonathan Haskell and Stian Westlake in Capitalism without Capital.

These authors highlight that the balance sheet drawn up under traditional accounting rules poorly reflects the overall value of a company because they understate the importance of intangible assets. This gap has been widening in recent years and is particularly noticeable in the world’s best performing companies. The five most valuable companies are worth £3.5 trillion together but their balance sheets report just £172 billion of tangible assets. Their intangible value amounts to trillions of dollars.

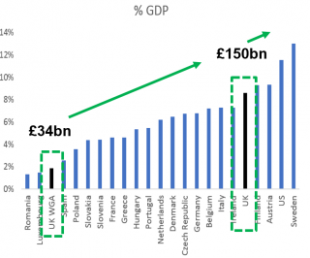

The picture in the public sector differs significantly. The measurement and use of balance sheets lag the market sector, although progress is being made. The OECD and IMF provide valuable overviews in recent papers on “Getting value out of accruals reform” and “Managing Public Wealth”. Understanding of Intangible Assets in the public sector is at an even earlier stage though economists at SPINTAN [1] have prepared experimental estimates. The chart below sets out SPINTAN’s conclusions for a range of countries.

Taking the UK government as an example, the accounting value of its intangible assets is £34 billion as recorded in its Whole of Government Accounts (WGA) whereas the SPINTAN estimate is £150 billion. However, even this larger figure may understate the true value of public sector intangibles. UK and other governments around the world have a long track record of delivering ground-breaking innovation. CT scanners – used in health systems all around the world - emerged as a collaboration between the UK National Health System and the music technology company EMI. US government laboratories played key roles in developing microchips and the internet, originally for the space and defence sectors, but with massive application beyond. Such innovations are not limited to advanced economies: the Rwandan Ministry of Health is developing innovative logistics pathways using drones to deliver medical supplies in partnership with a start-up.

A framework for value

Are these different approaches to valuing intangible assets just a measurement challenge, or can it add real value for fiscal policymakers and citizens?

In Measuring Capital in the New Economy (2005), Corrado, Hulten, and Sichel note many important questions surround the measurement of intangible assets. And the answers to them could lead to better assessments of an “economy’s long-run pace of economic growth and rate of technological advance, as well as to improved measures of national wealth”. In their introductory chapter, the authors conduct an extensive literature review highlighting the broad range of views in the measurement of intangible assets. This proved to be quite comprehensive as some researchers measured intangible assets as a residual (similar to total factor productivity), while others focused on the observed differences in human resource practices (including training) across businesses, while some explored the returns from R&D etc. Corrado, Hulten, and Sichel on the other hand set out a broader framework for the measurement of capital, and defined investment as any use of resource that reduced current consumption to increase future consumption. This allowed them to justify that spending on a range of intangibles such as brand equity, computerized databases, copyrights, improved organizational structures, and R&D etc should count as investment in company and national accounts.

For policymakers, developing frameworks to differentiate intangible assets from tangibles is crucial to getting the most out of them - and building the ground-breaking innovations that intangible assets enable. Haskel and Westlake set out four features (Spillovers, Synergies, Sunk costs, and Scaling up) which differentiated intangible assets from traditional asset classes, and a summary of their work can be found in a recent HM Treasury blog called The knowledge economy & innovation in the UK public sector. For example, a dataset might have very little value at first, but once combined with analytical know-how or infrastructure such as a cloud supercomputing, it can have a far greater impact.

Contrastingly, public sector management in most countries– financial and operational – usually operates within strong vertical structures. Ministries have defined purposes and limited pathways to work across silos. This does not encourage an assessment of how an investment made in one field could be combined with an innovation in another field (i.e. synergies). Or how a capability in one area can be scaled up significantly beyond a ministry’s core purpose. Justifying investment in managing intangible assets is difficult when it is outside an organization’s core mission.

Plan of action: establishing new pathways

The hidden value of intangible assets and the potential to increase economic, social and financial returns emerged as one of the biggest opportunities in a review the UK government carried out of its balance sheet in 2017. In 2018, HM Treasury published a report entitled “Getting Smart about Intellectual Property and other Intangible Assets”. The report made 10 recommendations aimed at realising greater value from knowledge assets held by the public sector.

A forthcoming implementation strategy document will set out how the UK government plans to implement these recommendations. Spending Review 2020 announced a number of specific investments of up to £17 million in 2021-22 to establish a new unit and fund that would focus on the last mile of innovation to help ensure that public sector knowledge assets (R&D, intellectual property and other intangible assets) translate into new high-tech jobs, businesses and economic growth.

Conclusion: creating opportunities

Adapting the value of intangible assets into the public sector creates several opportunities as well as challenges. It offers public sector financial managers the opportunity to be on the front foot regarding how the public sector innovates. It offers innovators within the public sector the opportunity to establish new financial underpinnings for their programmes. It offers citizens the opportunity to benefit from new productivity-driving innovations in the economy, and ultimately better public services, and the stronger public finances that result from this.

[1] SPINTAN (Smart Public Intangibles) is an EU funded project that has built a public intangible database for a wide set of EU countries.

[2] This article has been adapted from a blog at IMF Public Financial Management

Leave a comment